John Paul Jones, the often-reserved bassist and keyboardist of Led Zeppelin, offered a candid perspective on the inner dynamics of one of rock’s most iconic bands. Reflecting on the relationships among the members, Jones once explained, “We got along fine. The thing is, we never socialized. As soon as we left the road, we never saw each other, which I always thought contributed to the longevity and harmony of the band. We weren’t friends.” This seemingly surprising admission reveals a significant truth about Led Zeppelin’s internal structure: while their music was deeply collaborative and powerful, their personal connections were professional rather than personal.

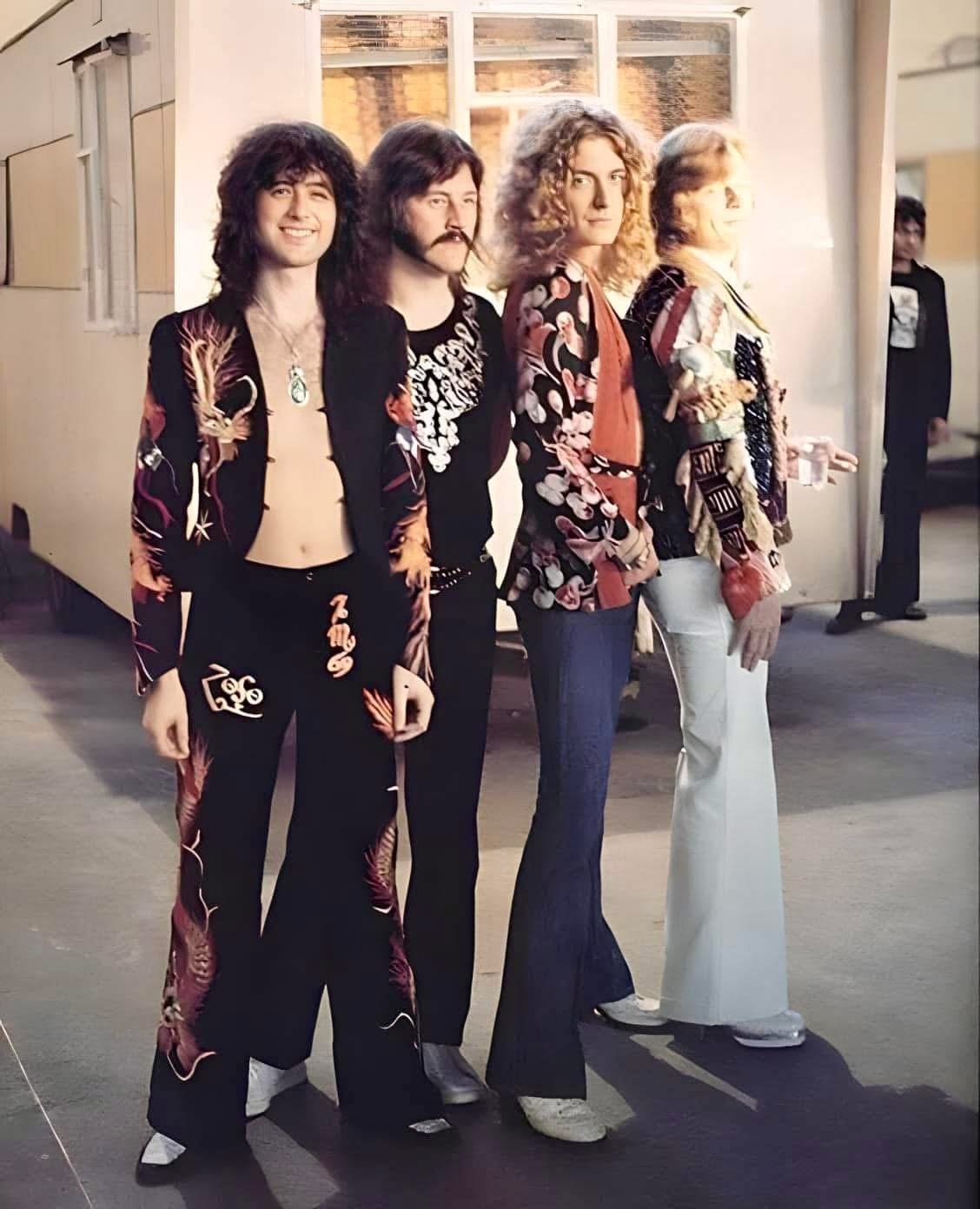

Unlike bands that formed through long-standing friendships or shared hometown roots, Led Zeppelin was assembled by guitarist Jimmy Page, who had a vision of creating something musically groundbreaking. “Led Zeppelin wasn’t manufactured exactly, but it was put together by Jimmy,” Jones explained. Each member—Robert Plant on vocals, John Bonham on drums, Jones himself on bass and keys, and Page on guitar—was chosen for their individual talents. The chemistry between them was electric on stage and in the studio, but that didn’t necessarily translate to offstage camaraderie.

Part of the distance between band members could be attributed to their differing personalities and lifestyles. While Page and Bonham embraced the stereotypical “rock star” lifestyle, full of excess, wild parties, and the unpredictable chaos that often accompanied fame in the 1970s, Jones and Plant tended to live more grounded lives. Jones, a veteran session musician before joining Zeppelin, was more focused on the craft of music and maintaining a relatively stable personal life. Plant, too, was known to seek refuge in family and rural living when not touring.

This split in personality types shaped the social fabric of the band. Page and Bonham were inseparable on the road, indulging in the hard-partying life that came to define much of the era’s rock mythology. In contrast, Jones often kept to himself, avoiding the more destructive aspects of the lifestyle. Despite this, the group functioned smoothly for much of their career, largely because their professional relationships were strong and their musical vision cohesive.

Jones likened the band members more to “workmates” than to “close friends,” a distinction that may seem odd given the intensity of their live performances and the intimacy of their music. Yet this sense of separation arguably contributed to their longevity. Without the burden of deep personal entanglements or interpersonal drama, they were able to focus on what mattered most: the music.

Indeed, this dynamic may have helped avoid some of the internal friction that plagued other bands of the time. The Beatles, for instance, famously suffered due to internal disputes between members who had once been close friends. In contrast, Led Zeppelin’s professional boundaries may have served as a buffer, allowing them to function effectively without letting personal issues derail the project.

In retrospect, Jones’s insight provides a rare and valuable look into how successful collaborations can work without deep personal bonds. It’s a reminder that artistic synergy doesn’t always require friendship—it sometimes requires respect, professionalism, and a shared commitment to the work. For Led Zeppelin, that approach produced a legacy of music that remains influential decades later, even if the bandmates were never quite the family fans imagined them to be.